Flaming orange threads, thin and precious, like a natural resource going scarce. Someone, in Iran, Turkey, Spain, India, bending in a field of crocus flowers, plucking each bloom from the earth with delicate fingers. 75,000 flaming orange filaments just to make one pound of this golden miracle. Each gram sold for as much as $15.

This is saffron, the world’s most expensive spice.

The crocus flower and its 3 orange-red filaments.

Etymology

There are two stories behind the saffron flower, and our poor protagonist dies at the end both.

There is an ancient Greek legend of Crocus and Mercury, who were dear friends. One day, the two friends were throwing a discus to each other. Mercury misjudged his throw and hit Crocus on the head, wounding him fatally. The young man collapsed and while dying, three drops of his blood fell onto the centre of a flower, which was how the lilac Crocus flower derived its three red filaments.

In another variation of the myth, the handsome youth Crocus sets out in pursuit of the nymph Smilax in the woods near Athens. Smilax is flattered by his amorous advances, but soon grows tired and resists his advances. Crocus, unable to get a hint, continues his pursuit. Irritated, Smilax finally puts an end to the whole affair and transforms him into a flower. Its radiant orange filaments were testimony to Crocus’ blazing passion.

The Seduction of Saffron

Highly prized saffron filaments

The world’s most expensive spice has gained patronage of history’s greatest names. Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, emptied a quarter-cup into her warm baths to benefit from its beautifying effects. She used it before commencing her liaisons with men, believing that saffron would heighten the pleasures of lovemaking.

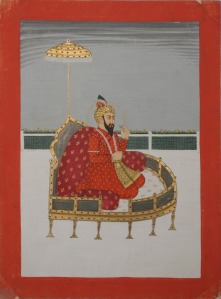

Saffron was also prized as a perfume by professional Greek courtesans known as the hetaerae. The hetaerae were not just prostitutes; they were independent and well-educated women renowned for their achievements in music and dance. They actively participated in the male-dominated symposia, where their opinion and presence were welcomed. In fact, the hetaerae of Greece were a lot like the courtesan-poetesses tawaaif of Mughal India.

In India, too, Saffron is considered a potent aphrodisiac. I’ve seen so many Bollywood movies where newly-wed brides carry into their nuptial chamber a cup of milk and saffron (kesar, as it is known in Hindi) for their husbands to consume. (Something that, admittedly, strikes me as a strange custom because it assumes that only men are entitled to experience enjoyment of the nuptial night. Otherwise, why don’t both parties get high on saffron and get on with it?)

Saffron infused with pure sandalwood oil is an ancient perfume blend, or attar, that is steeped in the romance and intrigue of India. Because of its prohibitively high cost, kesar attar was used only by royalty and the very wealthy. It was customary for Hindu Rajput brides in ancient India to be given this expensive oil as part of their dowry. The active ingredients, saffron and sandalwood, were and are believed to be aphrodisiac in nature. Upon wearing the perfume, a slight stimulation of the nervous system takes place, which in turn releases the right chemicals for love.

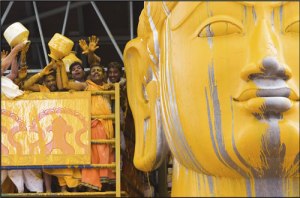

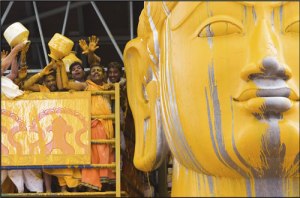

Bathed with milk and saffron. Photo by Karoki Lewis.

Saffron’s power is sacred, too. Roman and Indian deities have been offered saffron since ancient times. The Mahamastakabhisheka, an important Jain festival, is held in veneration of an immense 18-meter high statue. Since 978-993 AD, the statue has been bathed with milk, sugar cane juice and saffron paste.

Historically, saffron played an essential part in the arena of ancient medicine and magical potions. During his Asian campaigns, Alexander the Great used Persian saffron in his infusions, rice, and baths as a curative for battle wounds. The Persians themselves scattered saffron threads across beds and mixed them into hot teas as a curative for bouts of melancholy. The Sumerians used saffron as an ingredient in their remedies and magical potions. Egyptian healers, too, used saffron as a treatment for all varieties of gastrointestinal ailments. An ancient Egyptian treatment for stomach pain consisted of saffron crocus seeds mixed and crushed together with aager-tree remnants, ox fat, coriander, and myrrh.

The Soul of Saffron

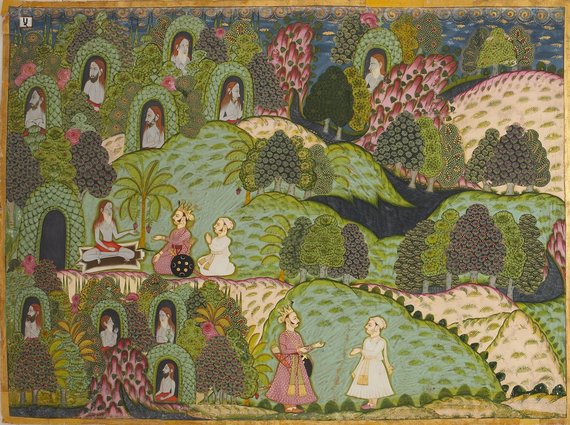

Mohammed Yusuf Teng, a poet and expert on the ancient culture of Kashmir, told BBC correspondent Daniel Lak* that “the indigenous people of Kashmir grew saffron more than 2,000 years ago, a fact that’s mentioned in the epics written during the era of Tantric Hindu kings.”

Saffron is ceremoniously used in Tantra, a mystical dimension of Hinduism, for awakening the kundalini (an unconscious, instinctive force or Shakti), which lies coiled at the base of the spine. According to one Tantric ritual I’ve come across in my research**, saffron is used in the basic ‘anointing’ of the Yogini. Jasmine oil is applied to her hands, patchouli to her throat and the pure essence of saffron to her feet.

This is saffron.

Associated with sex and romance, ancient potions and medicines, Queens and conquerors, the most expensive spice in the world comes to us through an intriguing, mysterious history riding on the reins of 3 fragile, flaming orange threads.

*http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/213043.stm

** http://www.rahoorkhuit.net/library/yoga/tantra/rituals/ritual_3.html